Colleges Grapple with Student Food Insecurity

Editor’s note: the following piece is cross-posted from Spotlight on Poverty & Opportunity.

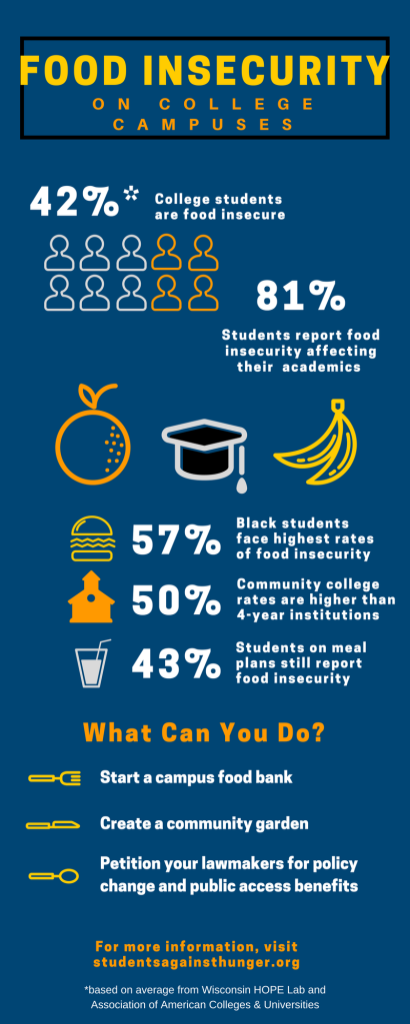

MISSOULA, Mont.: In the United States, nearly 13 percent of people are food insecure, living without reliable access to basic nutrition. But the problem is even more dramatic on college campuses, where a recent study found that 48% of students report food insecurity and live without regular access to food.

One solution campuses across the country increasingly are employing is on-campus emergency food pantries. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), in September 2018, more than 650 colleges reported having a food pantry on campus. Many of these pantries are charitably funded, operating with grants and privately raised funds and using donated food to stock shelves. Here in Missoula, the University of Montana Campus Food Pantry opened in February 2019.

“This is the fourth iteration of the idea of a pantry on campus,” says Katherine Cowley, a graduate student at the University of Montana and the pantry’s student coordinator. “The Basic Needs and Security Committee had been trying to address this issue for a long time, and finally the right people were in the room to get it done.”

In the two months since the pantry has opened, Cowley has served 49 individuals on this campus of about 10,000 students and has distributed 500 pounds of food. The pantry is located in the highly trafficked University Center, a building on campus that also houses the bookstore, the university cafeteria, and other student services. The visibility can be both positive and negative. While students can see the pantry and know it is a resource, Cowley often worries about stigma.

“When students come up, they are so apologetic. They’re nervous. Most have never asked for this kind of help before. I just tell them, I’ve been there. I lost my house last year. There have been periods I’ve been unemployed.” Cowley notes that her primary focus is access, adding, “I know if I put any barriers up, people who need the service are going to be missed.”

While emergency food is a necessary piece of a community’s food security infrastructure, many experts are cautious when institutional systems, like public education, look first to a charitable response to a lack of basic needs such as food access.

“I can see why [campus pantries] are seductive to student services staff, who are typically the people handed by this mandate,” says Janet Poppendieck, senior fellow at the Urban Food Policy Institute at the City University of New York (CUNY). “Because pantries are visible in culture – they [student services staff] can imagine one; it is not a huge lift to start one up. It’s not surprising that this has become a first response to this issue.”

Two decades ago in her book Sweet Charity?, Poppendieck questioned the institutionalization of the charitable food system. While honoring the hard work of those in pantries and food banks, she is among many anti-hunger advocates that acknowledge emergency food as a “band-aid solution” to an issue that is complex and systemic at its roots. In a recently-published letter in The Guardian, Poppendieck joined nearly sixty signers in stating, “Food banks are no solution to poverty.”

As in many developed nations, hunger is not an issue of food scarcity in the United States; rather it is an issue of income inequality, access to safety net programs, and the effectiveness of safety net policy.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the country’s most effective response to food insecurity, providing more than 40 million low-income Americans with monthly benefits to purchase food. For students in higher education however, the program can be difficult to navigate.

In Montana, and most states, in order to access SNAP, full-time students must work at least 20 hours per week or qualify for federal work-study. Part-time students often fall under the Able Bodied Adult Without Dependent (ABAWD) status, and are limited in participation to only three months in a thirty-six month period unless able to report 20.5 hours of work per week. And even eligible students often don’t take advantage of benefits. In a report released in January 2019, the GAO cites that while 3.3 million college students qualify for SNAP, more than half of eligible students do not participate in the program.

Accordingly, Poppendieck suggests one solution could be as simple as giving college support staff more training and expertise. Referring to SNAP, she says, “It is impossible to assume that [college] staff will just know the intricacies of this complicated program.”

Students believe the same. “I was never informed about SNAP by campus financial aid,” university student Tara Misers says. “I qualify for work-study, which means that when I have a work-study job, I qualify for SNAP. But this is something I had to learn from a food bank when my situation had gotten so bad I needed a food bank.”

Further complicating food security on campuses is that SNAP benefits can only be used to purchase unprepared foods. Students living on campus or in diverse housing, such as renting a room, can find it challenging to use food they are able to buy with SNAP because they lack appropriate storage or facilities to prepare food. For these reasons, many students are encouraged to purchase campus meal plans.

At the University of Montana, a meal plan costs undergraduate students $2,836 per semester. For those without the means to pay out-of-pocket for higher education, a student earning a four-year degree and participating in a meal plan all eight semesters will borrow $22,688 for food. Borrowing for basic needs, effectively charging interest on food, further encumbers exiting students with additional debt.

Tested policy approaches may be found within our existing education system, though not yet at the college level. In grades K-12, the federal government addresses food insecurity through the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program, and for children not-yet school-aged, the Child and Adult Care Food Program supports qualifying preschools and daycares. Through these anti-hunger responses, institutions receive a reimbursement for meals served to income-qualifying students. There is no such assistance program for students in college.

Several states have responded to the challenges that college students face accessing SNAP, however. Illinois, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and New Jersey have modified administrative rules to reduce barriers to benefits for full-time and part-time students. Rule changes include college enrollment as a qualifying activity to meet the job-training requirement for SNAP eligibility.

The widespread occurrence of food insecurity on campuses warrants a closer look at food access at a systems level. A charitable response is not a systems response, and while food pantries carry a necessary workload, experts like Poppendieck note that they can mask the widespread issue of food insecurity and decrease the urgency with which policy is responding. There is likely not a single solution that will relieve the food insecurity challenges of all affected college students. A multi-lensed response would be necessary to ensure that Americans pursuing higher education have access to basic nutrition.